By Duke Okes

It’s a given that not all audit nonconformities (NCs) are equal. Some indicate system weaknesses that could create life ending outcomes (e.g., hygiene issues in the food or healthcare industries), while others may simply be a minor documentation error (e.g., a class roster that was not signed by the course instructor).

Recognizing the relative degree of risk related to each NC allows an organization to better allocate resources where it makes more sense… another application of the Pareto principle. Even ISO 9001 indicates such when saying in the audit section 9.2.2.e), “take appropriate correction and corrective action…” and in the nonconformity and corrective action section 10.2.1.b), “evaluate the need for action…” and 10.2.1 “Corrective actions shall be appropriate to the effects…”

So corrective action might not be warranted for some NCs (e.g., correct the problem only), physical causes level for others, and root cause level for still others. Risk ranking can also help determine the relative timing allowed for corrective actions to be carried out as well as who should be involved in the investigation.

Unfortunately, too many organizations have simply adopted the binary classification of NCs used by most registrars, “Major” and “Minor.” While this is better than simply reporting it as a NC, it still does not provide much information. Of course, organizations may add other classifications to deal with audit findings where it is unclear whether the system needs work (observation) or where there are opportunities for improvement, but these do not help in ranking actual NCs.

The introduction of the term “risk-based thinking” in the ISO standard goes beyond simply replacing the preventive action requirements of the previous edition of the standard. It implies that throughout the management system risks can/should be considered when making decisions. This also concurs with senior management thinking that efforts should be placed where greater value can be achieved.

Some Examples

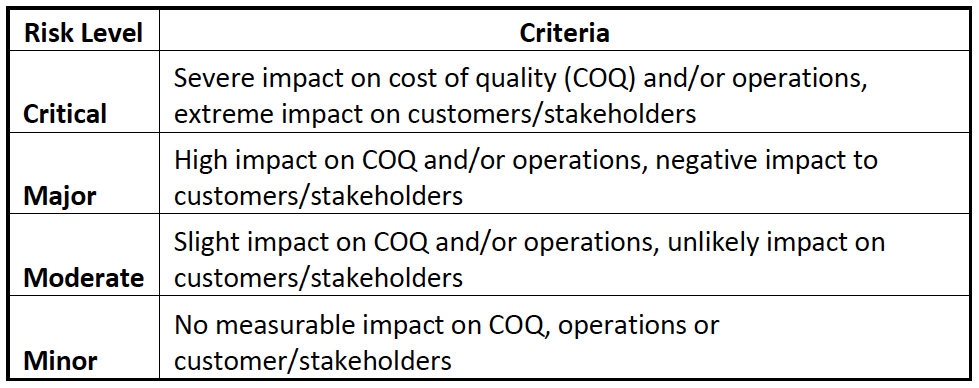

As part of courses on risk-based thinking and risk-based quality audits I have developed a simple NC ranking system (see table 1). Such an evaluation could consider risks to product/service quality, customer satisfaction, regulatory compliance, and/or other objectives or stakeholders.

A Google search uncovered a similar four-level NC rating system used by the Finance Division at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania. The levels are Nominal, Notable, Significant, and Major, with the level at which the issues should be resolved ranging from the staff of the department where found to involvement of Deans, and communications to the Board ranging from not at all to “in a timely manner.” Seriousness considers the financial impact, whether it involves a violation of laws or regulations, fraud, reputation, and others.

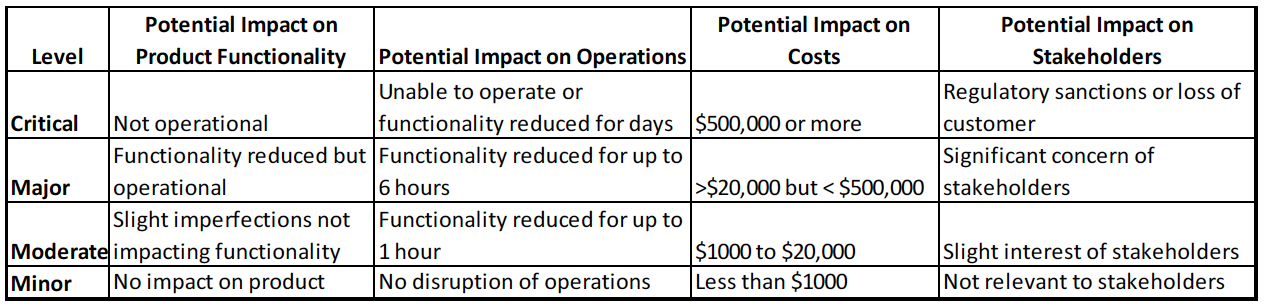

Some of the terms in table 1 are likely to be interpreted differently by each individual so in risk management programs a risk appetite table is often used to define risk levels in more specific terms. An example that could help auditors determine the appropriate level for each NC is shown in table 2. It requires a deeper evaluation of the potential impact of the NC on each specific objective.

Level Potential Impact on Product Functionality Potential Impact on Operations Potential Impact on Costs Potential Impact on Stakeholders Critical Not operational Unable to operate or functionality reduced for days $500,000 or more Regulatory sanctions or loss of customer Major Functionality reduced but operational Functionality reduced for up to 6 hours >$20,000 but < $500,000 Significant concern of stakeholders Moderate Slight imperfections not impacting functionality Functionality reduced for up to 1 hour $1,000 to $20,000 Slight interest of stakeholders Minor No impact on product No disruption of operations Less than $1,000 Not relevant to stakeholders

A similar concept has been applied to external audits in some industries. In 2012 the Global Harmonization Task Force released a guidance document (GHTF/SG3/N19:2012) describing a NC grading system that is being adopted by the Medical Device Single Audit Program (MDSAP). It identifies processes within ISO 13485 that are likely to have a direct impact on device safety and performance (e.g., product realization) versus that that would have an indirect impact (e.g., documentation). It also considers whether the NC is a first occurrence or a repeat of a NC found during recent previous audits. It then uses a 2×2 matrix of Occurrence and Impact to score the NC as 1, 2, 3 or 4. Additions to the score (called escalations) can also be made if the process is not adequately documented or if a nonconforming device has been released to the market. AS 9101 for the aerospace industry has a 3×3 process evaluation matrix that considers compliance versus results, and designates a score between 1 and 5.

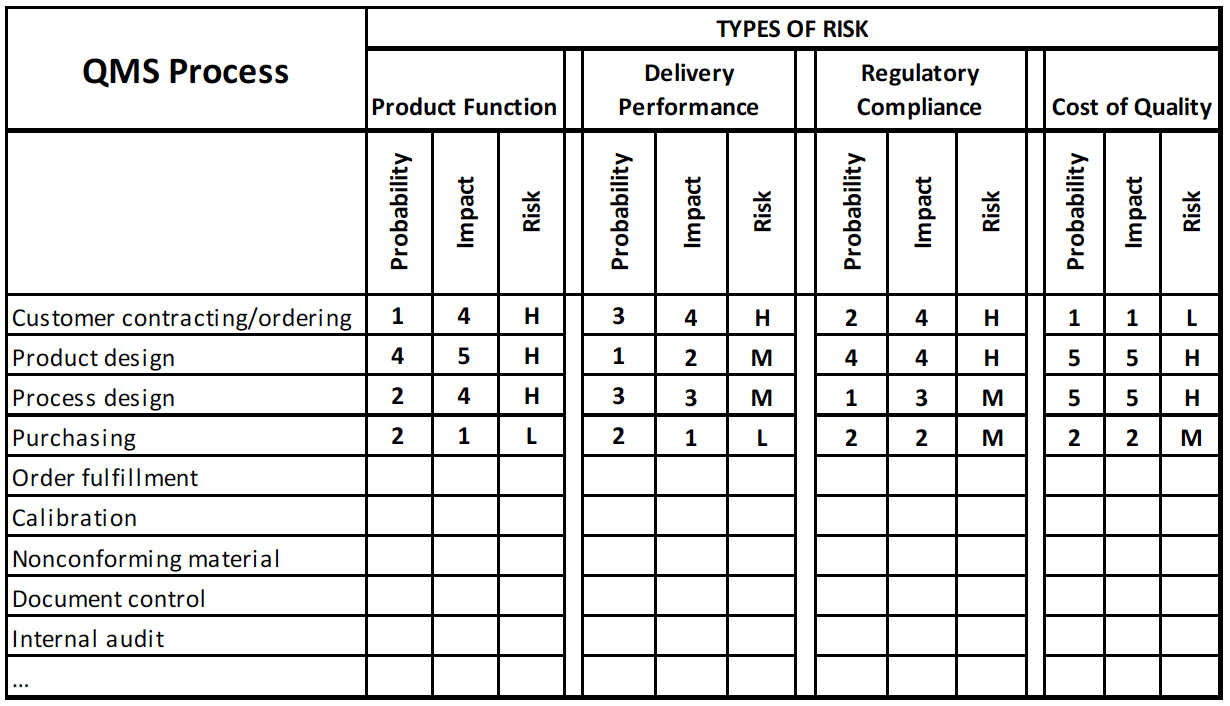

Quality audit managers who want to develop their own process-risk-focused ranking system might want to perform a risk assessment of processes in the QMS. Such an evaluation can also help prioritize other elements of the audit plan (ISO 9001:2015 indicates that audits should “take into consideration the importance of the processes concerned, …). Table 3 is a partial example, which demonstrates that for this organization some processes inherently have greater risk, meaning that they not only should be audited more frequently, but also that NCs in these processes have greater risk. As ISO 9001 points out, organizational context has a big impact on risk (in this organization all raw materials were supplied by the customer, which means Purchasing had little impact on quality performance). Such an assessment would ideally be conducted with input from process owners.

Aggregating Risks

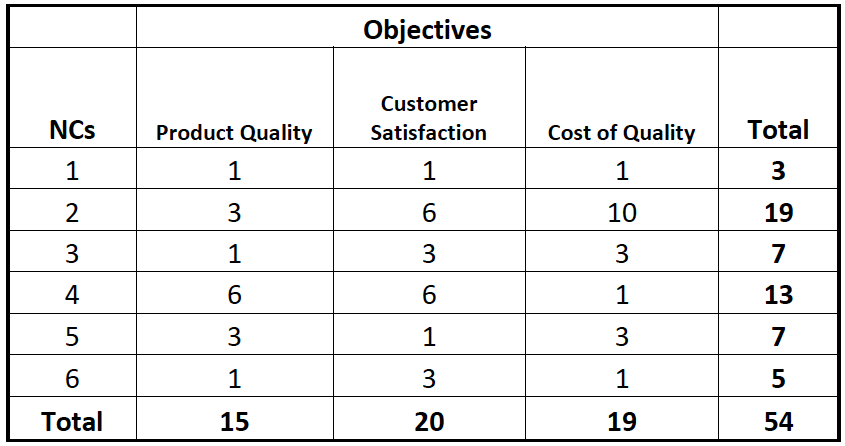

Of course, looking at single NCs may also cause the organization to not see the big picture. A way to aggregate risks might then add additional value. This is often done by department or process (see “Internal Audit Scorecards” in Okes, 2017), but a better way might be to show a matrix of all NCs found during the audit and the degree to which each aligns to objectives (see table 4). In this case rather than using words a number is assigned to each level using a nonlinear scale of 1, 3, 7 and 10. This helps better differentiate when the number of potential levels is low. Note that NC#s 2 & 4 are potentially more impactful, and customer satisfaction and COQ are the greatest overall risks related to this combination of NCs.

Another factor that could be considered for each NC is velocity. That is, if the potential impact on the objective turns into an actual impact, how long is it likely to take for it to show up? For example, will the impact on product functional performance show up at a final test station? Will it only show up after the customer purchases the car? Or will it be years before the degradation is evident?

Cautions

Internal financial auditors (often called GRC auditors—Governance, Risk and Compliance) have typically rated either the entire audit or each specific finding according to risk. Richard Chambers of the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA, 2017) indicates that this helps draw the attention of the board, as well as that of executive management. However, he also cautions about potential downsides:

- Process owners may take the ratings personally, especially if their performance reviews are impacted by audit ratings

- The ratings add time to generating the audit report

- Ratings can draw attention to some factors, with other factors perhaps being ignored or downplayed

Given that there are likely to be GRC, environmental, occupational health and safety, IT and other audits conducted in the organization, it would then be useful for quality auditors to consider how NCs are handled in these audits. After all, a fully integrated management system would include a fully integrated audit function. But if this integration has not already occurred, each group should at least be studying/benchmarking the others.

Summary

ISO 31000:2018 defined risk as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives.” When an audit is conducted it is evaluating the controls that have been put in place to reduce risk, and if those controls are not operating properly a NC is the immediate result. However, it is ultimately the objectives (quality objectives, organizational objectives, etc.) that is the primary concern, and ranking NCs according to risk then helps the organization better understand the relative degree of risks identified and how to respond accordingly.

The process of risk ranking and reporting NCs also needs to have its own controls, and it is hoped that the ideas presented herein will be useful in helping the reader evaluate the process at his/her own organization, as well as suppliers, customers and/or clients.

References

For the GHTF guidance document see: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/InternationalPrograms/MDSAPPilot/UCM468937.pdf

For the University of Scranton ranking method see: http://www.scranton.edu/finance/internal-audit/auditor-ratings.shtml

For Chambers’ IIA article see: https://iaonline.theiia.org/blogs/chambers/2017/Pages/Ratings-in-Audit-Reports-Lights-or-Lightning-Rods.aspx

For Okes’ book on Internal Audits see: https://www.amazon.com/Musings-Internal-Quality-Audits-Duke/dp/087389958X/ref=sr_1_10?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1497558274&sr=1-10

About the author

Duke Okes has been in private practice for 34 years as a trainer, consultant, writer, and speaker on quality management topics. His book titled Musings on Internal Quality Audits: Having a Greater Impact was published by ASQ Quality Press in 2017. He is an ASQ Fellow and holds certifications as a CMQ/OE, CQE, and CQA.

Copyright 2019 by Duke Okes. All rights reserved.