By Vincent Cafiso

Many of us in the quality profession are fully aware of and in most cases participate in our organization’s internal quality audit program. The internal quality audit program may simply consist of a local or site-level program broken up into a series of system, process and product audits conducted at defined intervals throughout the year intended to verify compliance of your organization’s quality management system (QMS) against applicable regulatory requirements. Or, if you work in a larger corporation with multiple business units/franchises and sites, you will also be familiar with a corporate or global internal quality audit program where corporate/global auditors routinely perform “FDA style” internal audits of your site to assess adherence to global policies and standards as well as verify compliance of your QMS against applicable regulatory requirements.

As quality professionals we should be aware of the value of a robust internal quality audit program. The U.S. FDA emphasizes this in the preamble to the Quality System Regulation (21 CFR Part 820): “…if conducted properly, internal quality audits can prevent major problems from developing…” and “during the internal quality audit, the manufacturer should review all procedures to ensure adequacy and compliance with the [QS] regulation, and determine whether the procedures are being effectively implemented at all times.”

The preamble goes on to state: “Manufacturers must realize that conducting effective quality audits is crucial. Without the feedback provided by the quality audit…manufacturers operate in an open loop system with no assurance that the process used to design and produce devices is operating in a state of control.”

A robust internal quality audit program will provide an accurate ongoing assessment of your organization’s compliance profile across the site (or sites) and operations, and that the programs and activities necessary to identify and address these recognized compliance gaps are implemented in an efficient, measurable, and effective manner.

However, in my experience performing hundreds of quality audits dating back to the early 1990s when I started my career as an investigator for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, I have seen that many organizations don’t see the value in establishing a robust internal quality audit program. Instead, they merely accept their regulatory obligation to establish and maintain an internal quality audit program (for example, to comply with such requirements as 21 CFR Part 820, section 820.22 Quality audit and ISO 13485:2016, section 8.2.4 Internal audit), but do so in a lackluster fashion implementing programs that merely “check the box” to comply with these regulatory requirements. Their internal quality audit process and procedures are ambiguous, and they employ subpar, lightly trained auditors who lack the necessary experience and qualifications to perform a thorough, value-added internal quality audit. Such programs fail to meet the high standards and value provided by a robust internal quality audit program.

Vision

So how do we ensure that our organization’s internal quality audit processes are robust, that auditor competency is nurtured, audit outcomes are actionable, and auditees are held accountable for their part in completing audit action plans to schedule?

First, we must determine what we are trying to accomplish with a robust internal quality audit program and establish an audit program vision. I suggest keeping the vision statement short but impactful, such as “Identify” and “Eliminate Compliance Gaps.”

The vision statement can then be further expanded upon:

- Through proactive, value-added internal quality auditing, identify and eliminate compliance gaps throughout the organization by leveraging the analysis of global internal quality audit data, assessment of risk across the organization based on this analysis, and predictive identification and communication of critical trends.

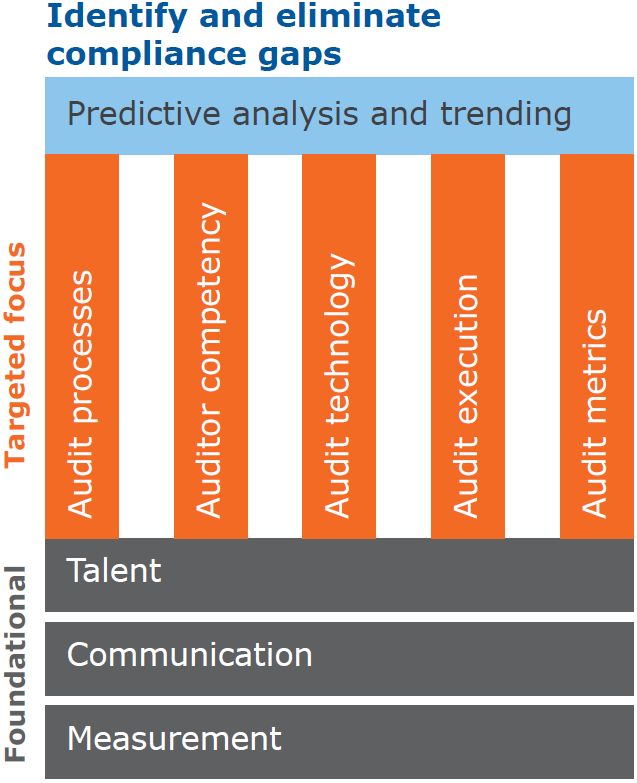

This vision is represented in figure 1 below:

Strategy

The internal quality audit program vision sets out to use the analysis of all sources of quality audit data (i.e., site/business unit/franchise internal, corporate/global, external/third-party, supplier) to identify unfavorable trends and eliminate recognized compliance gaps. This vision is supported by the following five pillars also shown above in figure 1 and encompasses an organization that is large with multiple business units/franchises and sites. This strategy can be scaled down for smaller organizations.

1. The strategy to achieve this vision considers all audit processes and starts with a process first approach—to standardize or centralize on one common corporate or global policy and procedure for how all internal quality audits are conducted across the organization. This will align the organization on a robust set of best audit practices and standardize the audit finding scoring and classification processes. This standardized approach to audit conduct, reporting, and scoring becomes important as we look above the pillars to predictive analysis and trending.

2. The next pillar is auditor competency. This is of the utmost importance since auditors are the impartial eyes and ears of the organization and serve as the link between the audit processes and audit execution. As such, the organization’s expectation is that auditors identify issues before external/third-party auditors. In this pillar, we set out to improve the “bench strength” of an organization’s quality auditors and provide them with the necessary training and support to do the best value-added internal quality audits. The organization expects that internal quality audits are as good as—if not better than—the most stringent of third-party audits (such as U.S. FDA and Notified Bodies). The shift toward highly skilled, expert internal quality auditors will give organizations a competitive edge within their industry as auditors identify issues and ensure actions are taken before they escalate to become costly regulatory actions that negatively impact customers (such as complaints, medical device reporting/adverse events, recalls).

3. The next pillar of Audit Technology will help to access all sources of audit data mentioned in the vision. Depending on the systems in use in your organization, audit data may reside within both electronic audit management software and local network drives used to house audit data for sites not using an electronic tool. If this is the case, collection of audit data from these various sources will be a combination of running reports and manual extraction. As a long-term plan to ensure all audit data are easily retrievable, organizations will need to secure the resources and discuss with key stakeholders across the organization the best options for software solutions for use by sites with a formal internal quality audit program. The software tool chosen will be used to house all forms of audit data across the organization such as site-level or local internal quality audit data, corporate/global audit data, as well as third-party audits from U.S. FDA, Notified Bodies, and so on. Supplier audit data may also be included in this system.

4. The Audit Execution pillar involves the constant monitoring of audit performance. This includes ensuring that internal quality audits are being scheduled and performed to schedule by trained auditors and auditees are being held accountable for their part in responding to audit requests and completing audit action plans to schedule. The Audit Execution pillar includes the local site and business unit/franchise-level internal quality audit programs as well as corporate/global internal quality audits of sites performed by a corporate/global audit group.

5. The final pillar of Audit Metrics encompasses establishment of metrics for all relevant aspects of the internal quality audit process, such as previously mentioned audit performance to schedule. Additional information will also be analyzed including the regulation/standard subsections identified in audit findings or nonconformities, how many major and minor nonconformities, action plan tracking (the number of actions open, complete, overdue) and finally the overall audit status (number of audits open, closed, duration open).

Resting on the structure and support of the five pillars described above is Predictive Analysis and Trending. Once the metrics have been established, those data can be analyzed for the interpretation and discovery of meaningful patterns or themes. Some patterns might be favorable, like sites with the least number of overdue actions. This can assist with benchmarking of positive processes and procedures that can be leveraged across the organization. Such data will also be analyzed to identify unfavorable patterns or themes that will prompt action; for example, high numbers of audit nonconformities across the organization concerning cleaning validation. Such situations can be escalated to quality management, who might create an appropriate “Cleaning Validation Task Force” to apply focused expertise and improvements in this area across the organization.

The pillars described above are securely fixed on a stable foundation comprised of TALENT, COMMUNICATION and MEASUREMENT.

Talent—All of the pillars require people who are the best at what they do, from audit policy to execution to data analysis. Existing training opportunities are constantly leveraged, and new opportunities are sought out to further enhance the skills and abilities of team members.

Communication is key—not only within the internal quality audit function and across functions but also across the broader organization. One especially important communication vehicle is through the formation of a community of practice such as a regulatory compliance network (RCN). This network should be comprised of site quality leader(s), audit program manager(s), lead auditors, auditors, and analysts. The RCN should meet regularly to collaborate on audit process improvements, deliver auditor training, discuss audit best practices and lessons learned, highlight FDA and industry compliance trends and developments. This regulatory compliance and audit specific content will further enhance the talent element above.

Measurement—Through the RCN, which is made up of compliance and audit subject matter experts, these five pillars can constantly be monitored, measured, and improved upon to ensure that all pillars continue to serve the organization and support the vision to identify and eliminate compliance gaps.

Finally, this vision and strategy will not succeed in a vacuum. It must be fully agreed upon and endorsed by the executives within your organization. With this agreement, executives will convey to their functional leaders their expectation of support for the internal quality audit program and provide the necessary resources. This will ensure that all key stakeholders involved take the necessary steps to ensure the internal quality audit program is implemented in a robust manner and that audits are value-added and identify and eliminate compliance gaps.

About the Author

Vincent Cafiso is a former FDA investigator. He is an expert in regulatory compliance, quality assurance, and quality systems. He has extensive experience in creation, maintenance, and auditing of quality system documentation for sterile medical devices and in vitro diagnostics (IVD) to ensure compliance with domestic and international quality and regulatory requirements.

Cafiso is also an experienced internal and supplier auditor having practical experience with FDA regulations and site inspection procedures. He has extensive experience in European and global quality system standards such as ISO 13485, ISO 9001, and the EU Medical Device Regulations (MD/AIMD, IVD). He has worked with numerous contract manufacturers to ensure that product is manufactured in compliance with U.S. and international quality system requirements.

References:

- Food and Drug Administration 21 CFR Parts 808, 812, and 820 Medical Devices; Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP)

- International Standard, ISO 13485:2016; Medical devices — Quality management systems — Requirements for regulatory purposes

Thank you so much Scott Paton for reprinting my LinkedIn article! I’m honored that you found it worthy to be posted on your well-respected and informative site.